The Ninjas

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Carcanet Press Ltd

Published:29th Nov '12

Should be back in stock very soon

Selected for Next Generation Poets 2014

Funny, heartbreaking, haunting: Jane Yeh's poems open windows onto utterly strange - and eerily familiar - worlds. Lonely ghosts hover around children on their way to school; lilies whisper among themselves, their heads 'filled with pollen and boredom'. Three solemn children in a Van Dyck portrait gaze out into their futures.

Moving between high art and pop culture, Yeh creates richly textured poems, their lyrical beauty cut with a dark wit. How do we face death, how survive loss? What does it take to carry on? 'O tempura, O monkeys'.

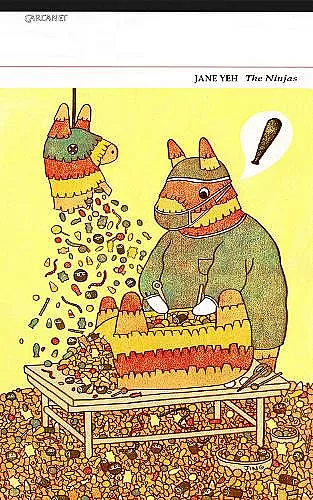

Jane Yeh's debut collection, Marabou (2005), which was nominated for the Whitbread Poetry Award and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, charmed with its cast of idiosyncratic voices, including an owl from Harry Potter and a flock of sheep about to be culled. The jacket of her second collection, The Ninjas, features a pinata carrying out an autopsy on another that appears to have been battered to death for its sweet interior. And as that might suggest, The Ninjas is just as eccentric as Yeh's debut, populated by androids, sentient lilies, yeti, kittens, talking portraits and, of course, ninjas.

It starts with the characteristically bizarre 'After the Attack of the Crystalline Entity', a poem that gives a voice to an android in an episode of Star Trek in which various colonies are destroyed by a huge crystal-like being. As peculiar as this sounds as a concept for a poem, Yeh gives her subject dignity, treating the fate of a servant android stuck on a post-apocalyptic planet with a gravity that such a circumstance would, in reality, merit, and ending with the haunting lines, 'This is an experiment on / Myself: how many days does it take / To give up waiting for anyone to come home?'. Yeh again shows her skill in inspiring ominous horror in 'The Night-Lily', which convincingly renders the flower into a (possibly carnivorous) monster, while the three poems on the forbiddingly named Deception Island in Antarctica also combine a sense of menace with taut economy: 'The snow falls as fast / As the heart pounding in your chest, until / Something comes to arrest it like love, only worse'.

Most of the poems, however, are more light-hearted; another android poem, for example, contains the fancifully humorous line, 'My first crush was a Roomba I mistook for a person'. The collection contains a group of poems that follow a set pattern of describing the characteristics of various creatures on the fringes of reality in impassive, end-stopped lines. The flat tone in which they deliver their often fantastic 'facts' is, again, charming, but the book would have been improved by omitting a few of them - their strangeness is of the same kind and can sometimes feel predictable. But a little excess is a small price to pay for this unashamedly and joyfully quirky second collection.

Jane Yeh's debut collection, Marabou (2005), which was nominated for the Whitbread Poetry Award and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, charmed with its cast of idiosyncratic voices, including an owl from Harry Potter and a flock of sheep about to be culled. The jacket of her second collection, The Ninjas, features a pinata carrying out an autopsy on another that appears to have been battered to death for its sweet interior. And as that might suggest, The Ninjas is just as eccentric as Yeh's debut, populated by androids, sentient lilies, yeti, kittens, talking portraits and, of course, ninjas.

It starts with the characteristically bizarre 'After the Attack of the Crystalline Entity', a poem that gives a voice to an android in an episode of Star Trek in which various colonies are destroyed by a huge crystal-like being. As peculiar as this sounds as a concept for a poem, Yeh gives her subject dignity, treating the fate of a servant android stuck on a post-apocalyptic planet with a gravity that such a circumstance would, in reality, merit, and ending with the haunting lines, 'This is an experiment on / Myself: how many days does it take / To give up waiting for anyone to come home?'. Yeh again shows her skill in inspiring ominous horror in 'The Night-Lily', which convincingly renders the flower into a (possibly carnivorous) monster, while the three poems on the forbiddingly named Deception Island in Antarctica also combine a sense of menace with taut economy: 'The snow falls as fast / As the heart pounding in your chest, until / Something comes to arrest it like love, only worse'.

Most of the poems, however, are more light-hearted; another android poem, for example, contains the fancifully humorous line, 'My first crush was a Roomba I mistook for a person'. The collection contains a group of poems that follow a set pattern of describing the characteristics of various creatures on the fringes of reality in impassive, end-stopped lines. The flat tone in which they deliver their often fantastic 'facts' is, again, charming, but the book would have been improved by omitting a few of them - their strangeness is of the same kind and can sometimes feel predictable. But a little excess is a small price to pay for this unashamedly and joyfully quirky second collection.

It's sometimes said of poems inspired by paintings that they seem too dependent on the knowledge of something very specific outside them to stand on their own feet. Nothing could be less true of a poem like Yeh's 'The Wyndham Sisters (after Sargent)'. It begins:

Their satin shapes foretell an ambassador's ball,

The fourth this season - such a dreadful bore. The long

Hand of evening comes forward as if to enfold them

Before the gas lamps go on. In the half-light their bodices

Softly glow, wrapped in oyster and ivory

Like expensive presents.

The sheer sensuous vividness of the writing is enough to make the poem an imaginative creation in its own right, but of course there's far more to it than that. For a start , the senses involved aren't limited to sight. 'Softly glow', for example, suggests the feel of the young women's bodices and their bodies, as well as visual impressions of light and colour. Time is injected in the first line, and the device of free indirect thought is used in the second to push us into the viewpoint of the sisters (this applies to 'softly glow' as well - if softly suggests what their clothes and bodies would be like to touch, 'glow' suggest the warmth the sisters themselves feel). By shifting between seeing the sisters from outside and seeing things from their own point of view the poet creates a kind of depth and ambiguity of suggestion that I would associate with sophisticated fiction more than with poetry. The tone changes sharply too, as in the swerve from the rapt voluptuousness of lines 4 and 5 to the tartness of line 6. Enjambments across strongly registered line endings heighten the sense that the angle of presentation is constantly changing. Later in the poem, Yeh will take us behind the actual picture in a kind of tracking shot round an 'outside' where houses disappear to infinity and the patrolman does his rounds, downstairs to the basement where the servants toil, then upstairs with the maids carrying trays, and to the ballroom door. In all these ways she pulls us through the picture surface and makes us imaginatively inhabit what seems like a living fictional space full of a fraught interplay between sympathy towards, detachment from and positive antipathy to its subjects.

This is just one of a number of fine poems based on portraits. They invite repeated contemplation, and offer new suggestions every time one looks at them. Almost equally fine are her animal poems. These have an affinity with the poems inspired by paintings by virtue of being portraits of their subjects, presenting them framed in a kind of temporal suspension, marked by the past, overshadowed by the future but not actually moving forward in time. There's a quite poignant contrast between our awareness of time (reading the marks of their history, imagining their future) and their own obliviousness of it (Yeh writes of her walrus 'It's almost comical / How unaware of the future he seems'). 'Almost comical' is telling. There's a great deal of comedy and wit, ranging from exuberantly cartoonish humour to the camp-tinged creepiness and beauty of the description of a night-lily that 'climbs at night / To infects my sleep with tendrils and strange music'. There's also a great deal of irony, both in the poet's tone and in her acute awareness of the ironies of life. Many poems are sad, disturbing and uncomfortable, often almost in the same breath as they're funny. They repeatedly suggest the inevitability of pain and loss, in the lives of the privileged no less than the lives of the oppressed. And there's a persistent sense of loneliness and incompleteness, felt by the android of 'Being an Android' ('Everyone admires my artificial skin, but nobody wants to touch it') no less than by some of the human subject. Even when they're not explicitly stated, I think alienation and incompleteness are suggested by how often the subjects are presented in terms that have them uneasily straddling worlds - the android yearning to be more human even as he surpasses humans in so many ways, animals described in ironically anthropomorphic terms, figures in paintings caught between the flowing of time and the stasis of art, with their hopes and fears mocked by what is to come. One particularly interesting image of alienation comes at the end of a poem inspired by the Pet Rescue TV series. This describes damaged animals restored to happiness in a kind of veterinary heaven where they also find cross-species friends and adoptive family. It's a poem about the overcoming of incompleteness and isolation but it ends with an image of the speaker staring at the television screen like Yeats' image of Keats as a hungry child with his face pressed to a sweetshop window:

There is love all around. Through the screen

I feel its warmth. I press my face against the glass.

Yeh's writing is much concerned, in richly ambiguous ways, with the gap between what art can imagine (whether the art be a Van Dyke portrait, science fiction or popular television) and what life delivers. Sometimes the emphasis falls on how life falls short of art, and sometimes on the warming and enhancing powers of the imagination.

She is a brilliant technician. Her acute visual sensibility, the sensuousness of her descriptions, her gift for the creation of striking metaphors, her sensitive orchestration of sound and the precision of her thought are all rich sources of pleasure for the reader. I hope I've suggested that there's also a deeper pleasure that derives from something like a vision of life running through most of the book. Admittedly there were a few poems I couldn't see as anything but technical exercises but even those poems that fail for me (perhaps through my failure to understand them) suggest a mind restlessly exploring technical and imaginative boundaries, and so contributed to my sense of Yeh's weight.

Jane Yeh’s The Ninjas is as unsettling and funny as its cover image by Jing Wei, ‘Foul Play’, affectionately known to the author as piñata autopsy. One is tempted to gobble down the exquisite poems one after another and yet these apparent confections mask a loneliness that creeps up the back of the neck. It is unusual to find such humour and sadness in one place; the nearest comparison might be short-story writer Lydia Davis whose tiny narratives delight with their lightness and clean phrases while hinting at vast, dark worlds beneath the surface.

One may not guess that Yeh is American (although there are peppered hints of accent) because the references to British places and popular culture are cited with the warmth and naturalness of a native. Yeh is now resident in the UK and so it is remarkable how Britishly deadpan is her humour. Having said that, there is something vaguely European about her love for the absurd, and the clarity of her language would be at home within a haiku. She is difficult to pin down, which makes her all the more fascinating. The poem' Pet Rescue' (on watching the daytime television show) ends with, 'There is love all around. Through the screen / I feel its warmth. I press my face against the glass.' Beauty, as well as humour and pathos, is in the mundane. The comic image of a face pressed against a television screen is also, somehow, unbearably sad.

There are moments in The Ninjas where darkness is the enemy, such as in 'Sequel to The Witches' (witches are recurring, malevolent characters) where 'I lie in my shed, listening to the spiders making webs, / Think I hear footsteps where they shouldn't be. / The goats rustle in their sleep, kicking imaginary tins. / Shadows creep up the wall like fingers, then suddenly recede,' but it is the whiteness of the icy desert that holds the most fear. The circular Antarctic island of Deception is the subject of three poems and one cannot help but feel that this cold world is a symbol of a self-imposed exile. 'The snow falls as fast / As the heart pounding in your chest, until / Something comes to arrest it like love, only worse.' Yeh's sharp lines are themselves like shards of ice.

Robots are recurring symbols in the collection. A lone android surveys a post-apocalyptic scene and attempts to entertain itself with experiments on animals, discovering that being 'masterless' involves greater responsibility. Another (or maybe the same one) practices cooking meals, which are eaten only by the cat. The easy, sweet tone of voice is touching and charming but again with an undercurrent of unease: 'Everyone admires my artificial skin, but nobody wants to touch it.' These android poems show Yeh's genius for portraying the outsider in understated, self-mocking language but in 'On Service', the 'robot' becomes human and the lightness of the previous poems only serves to intensify the darkness here. 'To lie down is a kind of paradise. The sheets / Are cold and thin against their legs... She clenches her hands in her pockets; they're crooked / From scrubbing. The future stretches out like a featureless plain / She can't see the end of. Her head aches from trying.'

Ekphrastic poems play a significant part in the collection and the images she chooses as subjects are perfect for her style and theme. They are portraits - staged and unnaturally posed - where the sitters are objects on display, to be observed by strangers' eyes, but Yeh cunningly inveigles her way into the minds of these sitters. The thoughts of the four 'Daughters of Edward D Boit' by John Singer Sargent are mundane and yet gently mutinous; in Manet's 'Olympia', it is the maid whose mind we enter, while Olympia is purely decorative, 'Her eyebrows frame a question that hasn't been asked.' In Sargent's 'The Wyndham Sisters', again it is the servants behind the scenes who hold the attention, and as for the sisters, 'How idle / Their hands are when emptied of fans.'

It is in he...

ISBN: 9781847771476

Dimensions: 211mm x 135mm x 8mm

Weight: 68g

80 pages