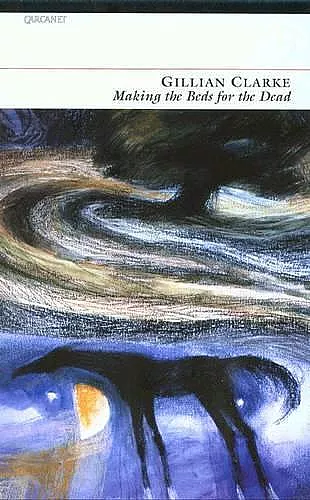

Making the Beds for the Dead

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Carcanet Press Ltd

Published:1st Apr '04

Currently unavailable, our supplier has not provided us a restock date

The title sequence of Making the Beds for the Dead charts the journey of a virus in 'the plague year'. Come from outer space, it travels - on a fox's paw, the beak of a kite and a crow and a buzzard - into the very heart of our lives. The poet includes personal, verses and stories from farmers in her family and neighbourhood.

The open structure allows the Gillian Clarke to include her seven rock poems, written for the National Botanic Garden of Wales; her poems based in archaeology; and her poems about war, and urban violence. There is an instinctive and a deliberate unity of theme and idiom in this book. The poet remains true to her landscapes and her nation. The sequence 'The Physicians of Myddfai', nine sonnets for Aberglasne, and much else is included in this characteristically generous and engaging volume by Wales' best-loved poet.

Reviewed in Planet by Anne Cluysenaar

This is a richly varied collection, remarkable both for its sense of vast perspectives within immediate (often homely) experience and its visceral evocation of current events.The role of art in our lives is another recurring theme, from the first poem, remembering the childhood impact of words and images in a Holy Bible, to the last, which imagines that, after some planetary flood (floods haunt this collection), the first colour to return "will be gold / one dip from Bellini's brush, / Cinquecento nativities..."

Reviewed by David Morley in The Guardian, 13th November 2004

All Clarke's books to date have an individual architecture in selection and order, one that requires her readers to grasp the book as a conceptual, even a musical whole.What we have here is no random collection.If you stand back from Making the Beds for the Dead you can spy an unusual and ambitious structure: eight "invisible" sections, some of which are self-contained sequences.The first opens with key motifs of alertness to language, and awareness of war, with the poem "In the Beginning" subtitled "on her 7th birthday".It's set during the final years of the second world war, and circles an image of "a desert land at war" and her own artistic awakening through the noise and imagery of the language of the King James Bible:

I see it all in colour, a girl my age

two thousand years ago, or sixty years

or now in a desert land at war, squatting

among the sheaves, arms raised,

threshing grain with a flail.

Threshing with a flail.That's it.Words

from another language, a narrative of spells

in difficult columns on those moth-thin pages,

words to thrill the heart with a strange music,

words like flail, and wilderness,

and in the beginning.

The motifs of desert conflict, and the Iraq war, recur throughout the book, even within an important sequence about the foot and mouth epidemic, the title poem.In this piece she makes an unforced and intellectually challenging connection between the suffering of Iraq and the suffering felt in rural communities of Wales.Not only that, but Clarke also uses what appears to be live prose accounts by rural workers giving their response to the foot and mouth crisis.These plain and moving accounts are snapped into, or traced into, lines within the sequence, and give it, and them, a great deal of dignity and sense of first witness, as in "Hywel's story":

"The 60s.I was out with a gun after rabbits, or a fox.

I walked to the end of the wood real quiet.I looked over the fence

at that secret field between the two woods.I was looking for mushrooms.

Something wrong with those cattle.They were lying down, standing,

any old how, alone facing the fence, heads down, not grazing.

Not together all one way like when it's going to rain."

This makes for honest scrutiny.One of the reasons manifest honesty can thrive in such a work, rather than just look swiped, is because Clarke provides such a strong structure to the whole sequence and book.It's the underpinnings provided by repeated design; there is a governing music to it all, a large patterning and a real eye for detail, and the "sound" of concision:

With block and tackle, grappling iron, axe,

they'd lift the lid off the lake.In a rare year

an acre could yield a thousand tons.

This kind ofmacro-architecture, familiar to any composer of music, taken together with the symphonic arc of the book, is entirely convincing and extremely impressive, but resists easygoing extraction, or excision for that matter.I'd urge you to defy traditional poetry-reading conduct ("let's dip into the book wherever") and instead walk the order of her mind as you would an expert garden.Gardens are total compositions; so is a book like this.Read her as a whole.Scant service is done to the readers of Gillian Clarke if they are guided towards the sound of a single birdcall while ignoring the involved orchestration of the entire chorus.

John Scrivener, The Reader, Issue 17, Spring 2005

Where the Future Believes in Itself

Straightaway in this new collection of poems by Gillian Clarke images of close-fitting accuracy arrest your attention: you're made to feel the 'moth-thin pages' of a Bible, or see a woman who, cutting into an apple, 'peels the fruit in a single / ringlet of skin': how exactly this gives us that coil of peel, at once tense and lolling (the single/ringlet repetition mimicking the repeating curls). Then later in the volume comes the little lamb 'an hour old, still damp and yolky' - again, how good 'yolky' is, not just for the slick of its fleece, but somehow for its wonky unsteadiness too, 'alive and up on trembling legs'. The poet's fidelity to the actual, which is a respect for the look and feel and smell of things (we have, like the lamb, to 'learn grass'), serves as an assurance to us, a baseline of trust, as does her willingness to alertly relax into the consciously humdrum, in the street maybe:

with the train drumming the viaduct

traffic turning up at the junction

We need the baseline of what we can make sure of, as does the poet herself, against the collection's background of freak floods and the scourge of foot and mouth, seen close up by the writer, who lives in rural Wales, as well as of larger disorders (the twin towers, the Iraq war, El Nino) which make the times seem out of joint. The fine poem 'The Flood Diary' blends to great effect personal experience and what is seem on television - she is truthful about the diverse and mediated ways in which we receive our impressions - while the title sequence 'Making the Beds for the Dead' traces the nightmarish progress of the foot and mouth virus through stories at first hypothetical, mythological even, but drawing closer to home, to your neighbours' animals, to your own, and the dreaded '...call at the door / of strangers dressed to kill'. If the poems dealing with 'nine eleven' and the Iraq war seem, to me anyway, to have less intensity of poetic life it's not because the attitudes they express is not decent and understandable, nor that they lack accomplishment, but rather, I think, that they treat of matters too remote, and lack this poet's touchstone of the real: the near at hand. The poem on the death of a specially-loved sheep ('"never name them", they warned') is more moving than that on the twin towers, not, of course, because more 'important' on some abstract scale but because closer and offering a more apprehensible form for sorrow.

Four sequences reprinted here originated in commissioned work, where we may be ready for bald patches, but these - especially 'The Stone Poems' and 'The Middleton Poems' - keep coming alive; here is a beautifully arrived-at moment of open reverie from 'Hay' in the 'Stone Poems' series:

Speaking of stone on a day like this,

the silence, the heat, the hay-days,

when the slates creak in the sun,

the flags are too hot for the dog

and the field's dried to a thin song

of seeds and grasshoppers,

yellow rattle, harebells, the litany of grass

The wings and songs of birds or pianos feel threatened in this collection. To take flight is dangerous: the poet is too aware of what 'can teach you gravity', and air is treacherous for those who

fall

like leaves, rubble, dust,

limbs akimbo on the air

as if arms could be wings

Fire and water are treacherous too in the time of floods and funeral pyres; only earth, or better still stone, is reliable, or water so frozen you can 'sever the tangled locks of waterfalls'. There may be safety in that fixity, and 'beasts stand as if stillness might rescue them'. This isn't just a temporary reaction; there is something more permanent in the poet's sense of ice 'reminding water / of the earth it came from'. It comes naturally to her to, so to speak, follow the blackbird's song back to its (proximate) source, to the 'bead of rain / in its throat'. The throat, the root, the dumb record of stone and fossil represent to the poet a kind of guarantee, perhaps because the future can sometimes more surely be felt in beginnings, as in the lovely poem 'Mother Tongue':

You'd hardly call it a nest,

Just a scrape in the stones,

but she's all of a dither

warning the wind and sky

with her desperate cries.

If we walk away

she'll come home quiet

to the warm brown pebble

with its cargo of blood and hunger,

where the future believes in itself,

and the beat of the sea

is the pulse of a blind

helmeted embryo afloat

in the twilight of an egg,

learning the language.

The poet seems to present us here with the claim, finally inscrutable, of life itself.

Richard Poole, New Welsh Review, volume 67, spring 2005

Gillian Clarke's new collection is made up of five sequences and twenty-seven poems split into three unequal groups. Her first book, a Triskel pamphlet entitled Snow on the Mountain, came out in 1971 and, after reading Making the Beds for the Dead, I dug out my copy. There were her characteristic early themes: domestic life, rural life, personal relationships, landscape, the beauty and brutality of nature. There too were her characteristic strengths: fluency, lucidity and a directness and simplicity of utterance that could at need generate a luminous sense of mystery.

Well, her new book still displays these themes and qualities, but poets must move on if they are to continue to write, and Clarke has moved on. Making the Beds for the Dead engages with both human and geological history, and is also deeply marked by contemporary events. There was, on occasion, disturbance in Snow on the Mountain, but it was contained within the realms of the personal. Now it has broken out to infect everything, threatening 'the way things are, / shifting the very ground /beneath our feet.' ('Marsh Fritillary'). At home there was the foot and mouth epidemic of 2001, abroad there was 9.11 and (still is) war in Iraq, while everywhere looms the imminence of ecological meltdown.

The opening group of ten poems contains some of the most attractive writing in the book. In 'In the Beginning' the poet recalls the excitement of being given an illustrated copy of the Bible on her seventh birthday, and the way simple but mysterious words took hold of her imagination:

words to thrill the heart with a strange music,

words like flail, and wilderness

and in the beginning.

'A Woman Sleeping at a Table' uses Vermeer's painting as a jumping-off point. This is the mid-seventeenth century, and science and exploration are opening up the world. Humanity has lost its innocence, and Clarke imagines the woman waking and peeling an apple, symbol of the Fall:

Undressed to its equator

it is half moonlight.

Then all white, naked, whole,

she slices to the star-heart

for the four quarters of the moon.

Four Sequences follow this first group: 'The Stone Poems' (ten poems), 'The Middleton Poems' (seven), 'The Physicians of Myddfai' (three) and 'Nine Green Gardens'. These are poems for whose material the poet has gone quarrying, and they wear their research on their sleeve. Not infrequently I felt that I was being fed information, even structured in a quasi-pedagogical manner, and I recalled Keats' dislike of poems that have designs upon us. 'The Stone Poems' is a trek through geological areas, and while Clarke wants us to share her awe at the big numbers she lays on us, her writing sometimes feels uncharacteristically clumsy. Experience in her best work is internalised and transformed, but the raw material of these sequences often seems undigested and external. This can be the case even within a poem. Compare the declension in intensity, the shift from poise to rhythmic flatness, in these stanzas from 'Plumbing':

A lemon bloomed with frost,

hollowed and filled with sweet snow.

A bowl of ice and Muscat grapes.

Breath on a glass of wine.

[...]

He piped water to his gate for public use,

to save the rural poor from filth and fevers,

a hundred years ahead of his time devised,

a water system for Carmarthen.

Is the comma after 'devised', one wonders, a misprint or a symptom?

Making the Beds for the Dead sometimes also has facts to convey, but its urgency and power derive from personal disturbance, so that if at times its writing is strained, strain is a sign of authenticity. Most of the poems refer to the foot and mouth outbreak of 2001, when Clarke's own holding was threatened, and they are by turns grim, bitter, angry, detached. Then, towards the end, the reader's surprised by a sudden expansion as international disaster breaks like a tidal wave over home concerns. It takes a very good poet to rise to the imaginative challenge of the images of 9/11 imprinted on us all, but Clarke does it in 'The Fall':

We watched them fall

like leaves, rubble, dust,

limbs akimbo on the air

as if arms could be wings,

as if men and women could be angels...

The enormity of this 'second fall from grace' both picks up the imagery of 'A Woman Sleeping at a Table' and reverberates through the strong group of five poems that closes the book. Here is war, here is the helpl...

ISBN: 9781857547375

Dimensions: 220mm x 140mm x 8mm

Weight: 118g

77 pages