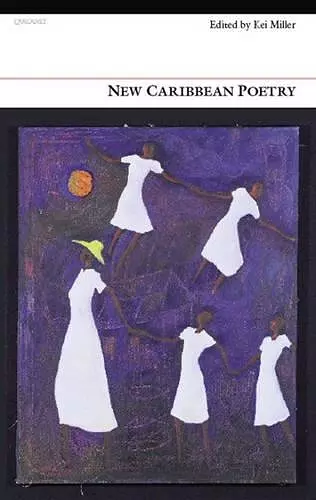

New Caribbean Poetry

An Anthology

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Carcanet Press Ltd

Published:31st May '07

Currently unavailable, our supplier has not provided us a restock date

The Caribbean is producing some of the most innovative and sophisticated poets in world literature today. This anthology turns the spotlight on eight New Caribbean poets. Between them, they represent the range of Caribbean identities and experiences: they are black, white, Indian and in between. Their first language is French, Spanish and English. They are home-bodies. They are world travellers. They represent all kinds of diaspora — from the islander who sought and made home in a foreign land, to the foreigner who sought and made home in the islands. The common thread between them is that they are all very good, and all are committed to the magical possibilities of language.

'These captivating poets write from the heart with poems which range from the spare and haunting to the risky and experimental. There are surprises, there is beauty, there are pleasures to be discovered, there is much to be enjoyed.'

Bernardine Evaristo

'A tremendous range of writing as excellent Jamaican poets rub shoulders with peers from Haiti, Trinidad and the Bahamas. Diverse and stimulating.'

Independent on Sunday

Vahni Capildeo on New Caribbean Poetry, ed. Kei Miller; American Fall, by Raymond Ramcharitar; and There Is an Anger that Moves, by Kei Miller

How to organise an anthology? Let us sample a few. The Oxford Book of Caribbean Verse (2005) is like a thick index to a timeline. By proceeding according to the poets’ birthdates, it shows neither the times when individual poets arrived at creating, nor how makers may be grouped, but their emergence strictly according to when the clock starts ticking on the body that will write. The Penguin Book of Caribbean Verse in English (1986) juxtaposes 'The Oral Tradition' with 'The Literary Tradition,' then skips happily over the divide, helpfully remarking on poetic reputation or self-definition, how page and performance interact. Breaklight, Andrew Salkey’s 1971 selection, sticks one scarlet-sleeved fist up at folk who insist that the poetic and the political should not trespass into each other’s territory (one thinks of that wavering line in the sea across which the Venezuelan and Trinidad coast guards have their shooting parties, but that is by the bye . . .). Breaklight groups poems by author, within five sections: 'The Concealed Spark,' 'The Heat of Identity,' 'The Blaze of the Struggle,' and 'Breaklight.' Two poems by Kamau Brathwaite form the epilogue. A little earlier, O.R. Dathorne’s Caribbean Verse (1967) has an implicitly politicised aesthetic, taking it as progress when landscape becomes an “instrument for change,” no longer “the passive object of the poet’s ecstasies”. Dathorne’s overt concern is for the authenticity of an indigenous “pastoral,” non-industrial, tradition. His Latin epigraph is from the eighteenth-century Jamaican poet and Cambridge-educated son of freed slaves, Francis Williams. Melanthika: An Anthology of Pan-Caribbean Writing, edited by Nick Toczek, Philip Nanton, and Yann Lovelock (1977) is of different scope. It is multiform, presenting prose fiction, essays, peer reviews, plus a survey of 'Caribbean Literary Magazines and Periodicals.' Its Caribbean is polyglot: 'English Language Writers,' 'Spanish Language Writers,' 'French Language Writers', and 'Dutch Language Writers.'

Remarkable about Melanthika is the number of direct appeals it launches. Throughout its pre-Internet pages the editors ask authors who have not been included to make themselves known; readers to send information about Caribbean print sources. These invitations — repeated till frustration or desperation edge the courtesy and hope — stand published. Melanthika’s editors encourage random word-freaks to chase them down. How things have changed since 1977.

How have they changed? There are personal notes regarding the production of two of the books under review. Raymond Ramcharitar, in American Fall, acknowledges both Wayne Brown and Derek Walcott’s kindness and guidance during and after his attendance at their workshops, then gainsays this, if only a little, in Young Poet, where the narrator recounts a Walcott-like figure’s slur:

. . . But he can’t resist a lick

in parting: “You Indians and your ambition. Black

people know how to relax, look at me.”

'Lick' could have its Caribbean meaning: a lash, a blow; or the senior poet could be using his rough bear-tongue finally to lick the cub-poet into shape. Either way, the savour is not sweet. Kei Miller, introducing New Caribbean Poetry: An Anthology, drops a sentence that chills my blood into hereditary uncharitableness: 'At a dinner one evening in Manchester, Michael Schmidt of Carcanet asked who were the exciting new poets in the Caribbean.' There swam to mind all my acquaintance who might be qualified to name 'exciting new poets in the Caribbean.' This vision emptied out as I considered how few might happen to find themselves (a) in Manchester and (b) at dinner with the not-powerless Michael Schmidt (poet, founder of Carcanet Press, and editor of Poetry Nation Review). Thank goodness, I thought, that the time of one air-letter per week and the boat home after five years is past — that this is the time of carbon footprints and instant communication — that a poet of Miller’s calibre is on the spot when a defining decision about

'New Caribbean Poetry' is taken around a table of cronies in the ex-colonial, manufacturing North . . .

Miller runs up a bright and modest banner for his 150-page selection. He presents the whole book as a transnational conversational venture, an answer to a friendly greeting:

It was also in New York that when old friends from back home kept asking, “Kei, what’s good?”, I could respond with the optimism they demanded: “Have you ever heard of Tanya Shirley? Jennifer Rahim? Christian Campbell? Ian Strachan? Marilène Phipps-Kettlewell? Loretta Collins Klobah? Delores Gauntlett? Shara McCallum?”

Here they are. Enjoy.

Naturally, anthologisers make claims for their creations — a thoughtful compiler is a creator. Pride and tradition, hard-won, prepared the way for Miller’s companionability and ease. Salkey (in 'Breaklight'), Shelleyan/Yeatsian, sends forth his poems/poets as an “unsung vanguard.” He hopes to say, “Yes. This is where I am . . . I am, indeed, at a point of departure . . . there is, now, not so much a corporate Caribbean ‘voice’ as differing voices from the Caribbean,” voices with implications for all humanity. This sounds brave, heroic, universal, and lonely. The Melanthika anthologists admit that their 'sampler' or 'cross-section' under-represents, for example, small islands, women, and 'smaller language and racial groups' because 'the problems of contact and communication alone made our task difficult enough.' Reading perversely, 'communication alone' might describe what a writer sometimes feels s/he does. May a Caribbean diaspora poet have a special sense of assurance that somewhere out there must be a likeminded reader or writer? Are we perhaps trained to cast a wide imaginative net — to feel that obstacles are superable, as the blue and green sea is readily cross-hatched with comings and goings, inventions, shocks, and remembrances? Would such a feeling suffice to power worthwhile writing? The formal teaching of 'creative writing' has its critics. Still, there is a notable enrichment of the habitat in which the new generation — Miller, Ramcharitar, and Miller’s writers — create, from shared attendance of workshops and events. Real contact and proximity, where two or three or more people are physically gathered together at moments that are chosen and by movement of their choice, not cold or forced migrations, not the sense of being salted into a historico-geographical barrel — this makes the difference: community of creation at a personal level. There is, too, another community of creation evident in this new writing — a spiritual community, quite unlike the revolutionary inflections of earlier work.

The anthologiser’s creation, the anthology, speaks for itself freely, and differently from how it is spoken about in its own introduction. There is fresh evidence in Miller’s New Caribbean Poetry of what Dathorne once found cause to praise Derek Walcott and Eric Roach for: a 'complete imaginative re-ordering.' These poets, if still, like their predecessors, haunted by the nameless bones beneath the ocean or sometimes moved by anger to an explicit rhetorical stance, inherit the world’s literature — rather, in embracing that potential inheritance, they create it.

The reader of an anthology, like the anthologist, is necessarily subjective. Here are a few points about each of the poets. Please encounter their work for yourselves.

Marilène Phipps-Kettlewell’s Sanctuary opens the collection, establishing the book as a hallowed conversational space. A reverberation runs from 'your hands a fragrant, needful folly' to Jennifer Rahim’s 'rose in the fragrance of heaven' (The Mango), four poems from the end. Phipps-Kettlewell resembles the American poet Denise Levertov, creating lyrics where exact, external vision and spiritual interiority fuse. Description and abstraction interpenetrate each other. Poetic artifice can be likened to a garment. Phipps-Kettlewell heals that separability. Readers of her poems momentarily inhabit their way of being, like a sacral investiture. Invitation and wonder speak: 'If it could be done, would you want / to be made into a frog?' (Frog); 'If I were to follow the only star on earth' (The Christ is Born); 'Come visit this life and enter' (Come Visit). The affiliation of the human and the natural, sentience and sentiments, is revealed even at the level of image: a lobster’s 'naked centre' is 'coiled pink like a heart prepped for Valentine' (Lobsters). This anthology’s poems answer each other. Hear cries out like St John of the Cross:

If so, come! Disarticulate me whole!

I want to feel your loving form,

to be pulled open and fall into a night that blackens all,

and throws me, vanquished, into your luminous desire.

Once there, I want to hear your Word, I want to know

who you are.

But also like the ardour of Delores Gauntlett’s The fever with which she danced; this passion could be of many kinds. The poems look beyond themselves, too. The adjective 'patriarchal' is quietly reclaimed (May You Live). Blue Eyes, with its god, fish, birds, face, ocean, sky, and memory, equally quietly re-engages with the anger of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and perhaps the elementality of Miller’s Granna’s Eyes sequence (from Kingdom of Empty Bellies, his first book of poems), to accentuate the positive:

It is in the eyes that

love rests and remains.

Gauntlett’s dry wit and intellect, expressed in pleasurable language, are a delight. The formal shapes of her stanzas enable the reader, not to face or endure, but truly to contemplate and confront, what might familiarly be called the unspeakable:

You’re a lucky man, they told him.

His eyes said not.

(Interview with a Centenarian)

There is something reminiscent of Mervyn Morris in her art. Morris-like is the eeriness with which Gauntlett figures, via tragic narrative, poetry’s own existence as a recurrent vanishing act of consciousness, as when

the stories clamber back, of the Kendal Ghost

emerging from the stricken stream . . .

(“Kendal Crash — 1957)

Like others in the 'new' generation, Gauntlett brings Caribbean men into poetry as they have not been before, and into richly domestic places which in poetic tradition have been gendered as feminine, but where in life men do belong. She writes 'probing,' like the subject of her Doctorbird poem, 'in the corner of my father’s garden.' The ease in handling tradition, in contrast to the strifeful utterances in earlier, pathbreaking anthologies, is again evidenced. In 'A Song for My Father', the reader enjoys a purely local Romantic expression of the moment of poetry as the surfacing of a yam that the narrator’s father suddenly digs up. The art of this poem is how it unfolds while a nightingale sings in the garden’s 'yam-vine quiet,' and is over, in one rapture of epiphanic synaesthesia, as soon as birdsong, dew, pimento scent are 'gone.' Much more could be said. Gauntlett is a poet to live with and re-read.

Christian Campbell’s poetry is, at first glance, more experimental than the previous two poets. Longer, slimmer stanzas go from page to page, unreeling dramatic monologues that have more novelistic, conversational room for humour and detritus observed with what remains a sense of beauty. One could name-check American poets, and Campbell himself re-writes Shakespeare’s John of Gaunt’s England speech, but there are grand Caribbean precedents for this poetry that tempts readers to read it aloud, perhaps break into self-forgetful and self-remembering solitary laughter in the airport lounge or library, giving the home accent to the 'who' for possessive 'whose':

. . . We always

have to pray every morning assembly

Our father who art in heaven

Harold be thy name and I ask you

why Harold so mean never to show

me his art? And the grin how you

answer is keep me glad for days.

(Shells for Sonia Sanchez)

This poem, with its child’s-eye detail, cuts to pathos and what, on a larger scale, is an outrageous truth. The island speaker has a too-late impulse to give his little all, 'shells and soldier crabs,' to the emigrant, because New York is 'far-far like the moon.' Generosity would send the island’s treasures away from it. 'On Listening to Shabba While Reading Césaire' uses the page like a performance space. Columns of words, words run together, ampersands, italics, capitals, make a shimmer of sound for the eye. Sound — whether church-style chorused responses or

How a New York cab could take me home to sun,

to Nassau, kweyol-pebbles beneath the tongue.

(Repatriation)

— is an unusually strong motive force in Campbell.

This is picked up in the next poet, Loretta Collins Klobah: 'It’s like there’s a soundtrack to this poem' (Going Up, Going Down). Trying to lyricise love between men, the poem finds it has to envisage the physical brutality of the homophobic Caribbean, so speaking outside this anthology to a major concern of Kei Miller’s new book, There Is an Anger that Moves. Collins Klobah’s poems are laced with Spanish language and social anger. She simultaneousl

ISBN: 9781857549416

Dimensions: 216mm x 135mm x 15mm

Weight: 227g

180 pages