Collected Poems

Henry Reed author Jon Stallworthy editor

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Carcanet Press Ltd

Published:26th Jul '07

Should be back in stock very soon

WITH A FOREWORD BY FRANK KERMODE

Henry Reed (1914-86) is most familiar as the author of 'The Naming of Parts', the best-loved and most anthologised poem of the Second World War. He was a poet of much greater scope than that: in addition to publishing A Map of Verona, his 1946 collection, he was a fine translator, particularly from the Italian, and wrote acclaimed radio plays, including an ambitious adaptation of Moby-Dick and a series of six plays featuring his comic creation Hilda Tablet. On his death he left a sheaf of uncollected poems that had appeared in magazines or were in manuscript. These, together with all Reed's published work, a group of translations and a selection of songs from the radio plays, make up this Collected Poems. Jon Stallworthy, poet, critic and biographer of Wilfred Owen, has included a biographical and critical introduction to this profound, witty and humane poet.

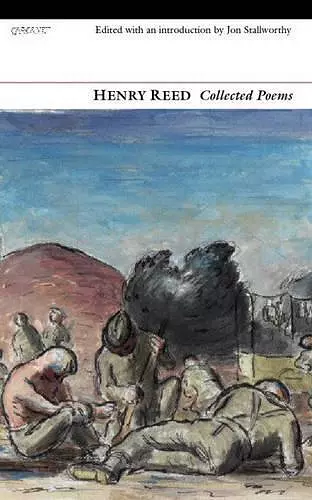

Cover image 'Troops Resting' (detail) by Edward Ardizzone. Crown copyright, reproduced by permission of the Imperial War Museum.

The most ambitious contemporary poets tend to be haunted by the ridiculousness of poetry, its irrelevance, its pretentiousness, the selectiveness of its attention and the kind of focus required for its reading. 'I, too, dislike it,' Marianne Moore's three-line poem 'Poetry' begins: 'Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers in / it, after all, a place for the genuine.' Because poetry is always tempted to pose as poetry rather than to say or sound like something unusual and interesting (i.e. genuine), it is often on the verge of self-parody. It's this that gives the best modern poetry its edge. Unlike prose writers, poets are like stand-up comics; their bad lines are dangerous because there are worse things than being ignored. Poetry is always high-risk because of the mockery that is always around, especially in the poet himself.

So it is not incidental that much of the most remarkable poetry in the late Henry Reed's wonderful Collected Poems sounds like his famous parody of Eliot's Four Quartets, 'Chard Whitlow': 'As we get older we do not get any younger. / Seasons return, and today I am fifty-five / And this time last year I was fifty-four, / And this time next year I will be sixty-two.' Poetry as the ordering of experience is implausible for Reed, a grand banality that he implies Eliot was tempted by to assuage something more distraught in himself.

It is not just that Reed uses Eliot's language against him, but that he knows that the most serious things we say often tip us over into something else and that poetry is very good at telling us what words can't do for us. In his poem 'Tintagel', he writes: 'We cannot learn to forget as sometimes we learn to remember. / To compose an oblivion like a memory. / To capture carefully an empty future.' For Reed, poetry was the art of the insoluble, of the quest that is only interesting because it fails.

Reed has a plain eloquence for what goes wrong and for what then holds absurdity at bay. In 'The Door and the Window', a love poem about an absent lover, he writes of 'Waking to find the room not as I thought it was, / But the window further away, and the door in another direction', as if the room (or the lover) in the world should match the room in the mind and that only in language can a door change direction or have any direction at all. Reed wants to show us, without melodrama, how disoriented we are by what language lets us do, what language lets us notice: 'It is not that courage has risen,' Antigone says in Reed's poem of that name, 'but that fear has failed for a moment.'

Excellently edited by Jon Stallworthy, and with an intriguing new foreword by Frank Kermode, Reed's small body of work - one book published in his lifetime, A Map of Verona (1947), when he was 33, and many good uncollected poems and fragments - has the kind of sly subtlety and odd tone that makes him such an unusual voice in postwar British poetry. You often get the sense, reading Reed's poetry, not that seriousness in poetry can be all too easily mocked but that seriousness itself can be a form of mockery. Reed, Kermode writes, was 'a sad but a funny man and his poems are funny or sad'. His poems are at once so compelling and so puzzling because they are never quite sure which is which.

ISBN: 9781857549430

Dimensions: 216mm x 135mm x 15mm

Weight: 249g

190 pages

2nd edition, replaces previous.