Body Language

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Carcanet Press Ltd

Published:30th Sep '04

Should be back in stock very soon

Body language and the body of language—from the first words in the first garden to the last words of last night’s lovers—are the entwined themes of Jon Stallworthy’s new collection of poems, his first since The Guest from the Future (1995), described by Poetry Review as ‘snatches of radio traffic from this century’s storms, true stories... and some of the storytelling inspired’.

The centrepiece of the book is ‘Skyhorse’, an ambitious poem for voices that finds in the White Horse on the Berkshire Downs an enduring presence through the turbulence of three millennia of English history. Generations of devotees and riders of this English Pegasus speak of bodies changed by love and war, leading to the book’s second part, a candid, passionate sequence of elegies and love poems.

Anne Berkeley, Oxford Poetry, Issue XII, Spring 2006:

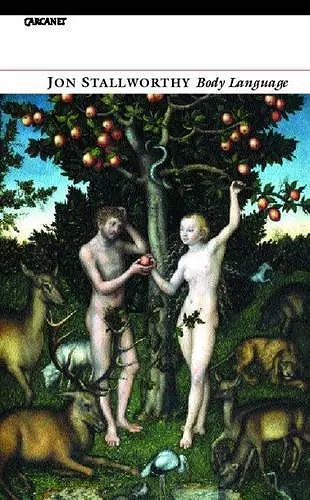

On the cover of Jon Stallworthy's new collection, Lucas Cranach's Eve offers Adam the bitten apple. Behind them, a white horse steps out of the darkening undergrowth into the first poem:

emerging from the undergrowth,

a moon-white creature woke

the man's still-sleeping heart. It stirred,

and set his tongue to groping for the Word

the Garden Master spoke,

creating what came nearer as its name

receded from the listener and

was lost. The nameless nudged his hand.

'Horse,' he said, 'horse.' But it was not the same.

('In the Beginning')

The Horse dominates the first section, Language. In 'Skyhorse', as ambitious and versatile a sequence as any he has attempted, Stallworthy addresses the human need to create, praise and lament. Inspired by the White Horse at Uffington (a 'calligramme'), he hears 'a voice / I knew and did not know / as mine.' When, c.1000 BC, the lightning-struck priest receives his commission to carve the horse, the story is told in spare, free lines. By the time the horse is made and the priest dead, the verse has taken shape in two-stress, seven-line stanzas, slicing a line clean down the page, stamping its repetitions in funeral rites. Anglo-Saxon rhythms and alliteration mark the battle of Aclea in AD 871, and there is a lovely change of cadence for the 13th century Wandering scholar's troubadour measures:

May morning and a marvel

I climbed a hill to see,

when hedge choirs were singing

of love, but not to me.

(Section 4)

Voices sound through the ages: heroic couplets for an 18th century Antiquary, music-hall oompahs for Hippisley's Brass Band in 1905. War predominates. The deftness is somewhat marred by an unconvincing rifleman. The sequence culminates in a millennial round-the-world nightmare ride, in a 'wind...sticthed with voices' (the notes are helpful) over the killing-grounds of a 'murderous century', before the poet sets off downhill 'into a future not foretold.'

The sequence is framed by two masterly poems, one cosmic, one domestic. If the rhymes seem unforced, it's not because the thought is unsubtle.

Newdigate Prizewinner, Norton anthologist, critic, prizewinning biographer of Owen and MacNeice, Stallworthy handles rhyme with the ease of a lifetime. He is 70 this year, with a new bluntness born of loss, recollecting the time when "the sun still / would lift itself off its arse / without a white pill" ('Hunting the Lark'). The white pill has morphed from the 'the white pillow' in the 'Artic light' of the previous poem. 'Write it down and drive it away,' the Exorcist used to urge.

If Language is more political, Body is concerned with 'the luggage of love and grief.' It, too, opens in a garden, but:

If only I could learn

from the Russet to let my leaves go

downwind to the bonfire and so

sweeten the village as others burn

bitterly. We are at war

again, but laughter can be heard

above the axe in the orchard,

wheels slowing at the door.

('Before Setting Out')

The Chekhovian note is followed by a series of elegies. A villanelle for his father urges understanding - not rage - against 'The White Cloud' shadowing them.

There are some fine poems here, to stand alongside his best. 'The Motor Vessel Anichka', which initiates a riff of love poems, charms with its open affectiomn, celebrating coupledom in a nod to Inisfree's solitude (and arguably, echoes of Marlow and Masefield, Wordworth, Whitman and even Lear). Hecht would have loved the 'rhyming cascade' of 'Hunting the Lark'. There are sparky translations from Mandelstam and Broniewski.

'Body Language' suggests wordless communication, perhaps an ideal where 'hands that were strangers talk as twins / with no word spoken.' 'In the Beginning', Creation is 'God's poem', a series of speech-acts. The closing poem offers an alternaive poetics. 'In the House of the Poet' the archaeologist's hammer taps the petrified remains of a Pompeian victim:

'breaking the pumice skin, / letting the dark out, / letting the light in.' In the first poem, man and woman stand looking at each other; in the last, they are sealed in separate tombs,

and all those poems lost

but one (the last) in mis-

translation: this.

Creation or discovery - poetry brings to light, out of silence, what may or may not have existed before the words were put together. In honouring what is lost, Stallworthy makes it new.

Anne Berkley,Oxford Poetry XII, Spring 2006

‘Pale Horse’

On the cover of Jon Stallworthy's new collection, Lucas Cranach's Eve offers Adam the bitten apple. Behind them, a white horse steps out of the darkening undergrowth into the first poem:

emerging from the undergrowth,

a moon-white creature woke

the man’s still-sleeping heart. It stirred,

and set his tongue to groping for the Word

the Garden Master spoke,

creating what came nearer as its name

receded from the listener and

was lost. The nameless nudged his hand.

'Horse,' he said, 'horse.' But it was not the same.

('In the Beginning')

The horse dominates the first section, Language. In 'Skyhorse', as ambitious and versatile a sequence as any he has attempted, Stallworthy addresses the human need to create, praise and lament. Inspired by the White Horse at Uffington (a 'calligramme'), he hears 'a voice/ I knew and did not know/ as mine.' When, c.1000 BC, the lightening-struck priest receives his commission to carve the horse, the story is told in spare free lines. By the time a horse is made and the priest is dead, the verse has taken shape in two-stress, seven-line stanzas, slicing a clean line down the page, stamping its repetitions in funeral rites. Anglo-Saxon rhythms and alliteration mark the battle of Aclea in AD 871, and there is a lovely change of cadence for the 13th century Wandering Scholar's troubadour measures:

May morning and a marvel

I climbed a hill to see,

when hedge choirs were singing

of love, but not to me.

(section 4)

Voices sound through the ages: heroic couplets for an 18th century Antiquary, music hall oompahs for Hippisley's Brass Band in 1905. War predominates. The deftness is somewhat marred by an unconvincing rifleman. The sequence culminates in a millennial round-the-world nightmare ride, in a 'wind…stitched with voices' (the notes are helpful)over the killing-grounds of a 'murderous century', before the poet sets off downhill 'into a future not foretold'.

The sequence is framed by two masterly poems, one cosmic, one domestic. If the rhymes seem unforced, it’s not because the thought is unsubtle.

Newdigate Prizewinner, Norton anthologist, critic, prize-winning biographer of Owen and MacNeice, Stallworthy handles rhyme with the ease of a lifetime. He is 70 this year, with a new bluntness born of loss, recollecting the time when 'the sun still/ would life itself off its arse/ without a white pill' ('Hunting the Lark'). The white pill has morphed from the 'the white pillow' in the 'Artic light' of the previous poem. 'Write it down and drive away,' the Exorcist used to urge.

If Language is more political, Body is concerned with 'the luggage of love and grief'. It, too, opens a garden, but:

If only I could learn

from the Russet to let my leaves go

downwind to the bonfire and so

sweeten the village as others burn

bitterly. We are at war

again, but the laughter can be heard

above the axe in the orchard,

wheels slowing at the door.

('Before Setting Out')

The Chekhovian note is followed by a series of elegies. A villanelle for his father urges understanding - not rage - against 'The White Cloud' shadowing them.

There are some fine poems here, to stand alongside his best. 'The Motor Vessel Anichka', which initiates a riff of love poems, charms with its open affection, celebrating coupledom in a nod to Inishfree's solitude (and arguably, echoes of Marlowe and Masefield, Wordsworth, Whitman and even Lear). Hecht would have loved the 'rhyming cascade' of 'Hunting the Lark'. There are sparky translations from Mandelstam and Broniewski.

'Body Language' suggests wordless communication, perhaps an ideal where 'hands that were strangers talk as twins/ with no word spoken.' 'In the Beginning', Creation is 'God’s poem', a series of speech acts. The closing poem offers an alternative poetics. 'In the House of the Poet' the archaeologist's hammer taps the petrified remains of a Pompeian victim:

'breaking the pumice skin,/ letting the dark out,/ letting the light in.'

In the first poem, man and woman stand looking at each other; in the last, they are sealed in separate tombs,

and all those poems lost

but one (the last) in mis-

translation: this.

Creation or discovery - poetry brings to light, out of silence, what may or may not have existed before the words were put together. In honouring what is lost, Stallworthy makes it new.

ISBN: 9781857547467

Dimensions: 216mm x 135mm x 5mm

Weight: 86g

64 pages